I joined RenewableUK in June 2012 and left in March 2019. This blog post provides some reflections on my time with the organisation. To hear my thoughts on a wide range of issues, head to the Cardiff Podcast where I chat about climate change, feminism, the energy sector in Wales and my new venture, Afallen.

Today marks the end of my employment with RenewableUK, the UK’s pre-eminent not-for-profit trade body for clean energy, and the only one with a staff presence in Wales. Nearly seven years after my move from the European Environment Agency in Denmark, I’m taking my next steps in my career — this time, one that I’ve defined for myself (more on that in a future post!)

I’m taking the opportunity to reflect on some of the changes that have taken place over those seven years, and on the challenges that lie ahead. After all, although renewables are now one of the dominant forms of electricity generation, we still have to get to grips with powering our transport and heat with renewable energy if we’re to have any hope of meeting our legal and moral obligations to a low-carbon society.

The change

The sector has seen astonishing changes over the last seven years — both at a UK level, and in Wales. Most interesting for me is the change in political and media attitude to renewables over that time, and the divergence in approach to renewable energy between the governments of the UK and Wales.

‘Renewables’ in the media is usually a proxy to talk about onshore wind, a technology supported by the vast majority of citizens of the UK (demonstrated time and again by UK Government polls), yet one described almost invariably by the media as ‘controversial’. Perhaps in the same way as brussel sprouts on the plate at Christmas being ‘controversial’, in that a tiny proportion of the population are highly exercised by it; but not in the least controversial across the population at large.

Despite my continuing frustration with many media outlets about their representation of onshore wind, the situation in Wales has greatly improved. In 2012 the general tone of debate was hostile, with a number of journalists — yes at some small publications, but also at national outlets — making little secret of their hostility. Perhaps this was partly down to the extreme politicisation of the topic, most notably by Russell George and Glyn Davies, which led to the famous protest outside the Senedd in 2011.

However, onshore wind has now become accepted by most communities and the media in Wales as infrastructure necessary for the benefit of future generations. Again, as a proxy for all renewables, this is extremely important, because without widespread acceptance, we cannot take the steps we know are necessary in order to prevent the very worst impacts of climate change.

This is not to say that questions around the appropriateness of onshore wind are still not leveled — listen to my recent interview with Radio Cymru (with subtitles) where I field the assertion that wind turbines are ‘ugly’ — but this tends to happen less frequently.

Policy

Policy in Wales has also seen huge changes over that time. Those with long enough memories will recall the discussions around the Silk Commission, and transfers of powers for consenting energy projects to Wales from Westminster. Indeed, our own members were not convinced by the idea, some preferring the idea of UK Ministers making decisions over the ‘lottery’ of local authority or Welsh Minister determination.

How times change. In the intervening years, in Wales, we have witnessed the adoption of the Environment Act and the Well-being of Future Generations Act and — today — the launch of the low carbon delivery plan. And simultaneously at the UK level, we’ve seen a cooling of support for funding renewables generally, and a huge political and policy surge for that most unpopular of technologies, fracking. As I put it in 2016, Wales and England seem to be very different shades of green.

Our members would, I suspect, strongly oppose any idea of consenting powers for energy projects making their way back up the M4. I posed the question in 2015 as to whether decisions taken by the UK Government were making nationalists of the business community. Certainly, insofar as the direction of travel of sustainability, their policies may well have had the impact of shoring up support for the institutions of government within the devolved administrations.

Wot no lagoon?

Probably the biggest disappointment during my time at RenewableUK was the decision by the UK Government not to provide financial support for the Swansea Bay Tidal Lagoon project, at the same time as it was bending over backwards to guarantee eye-wateringly lucrative payments for the nuclear sector (and yes, the evidence shows that a policy environment supportive for nuclear is less supportive for renewables)

In 2015 I wrote — before the outcome of the Hendry review was known — that a Wales without lagoons would be poorer, dirtier and sadder. When the review was finally published by UK Government, it described supporting the Swansea project as a ‘no regrets’ option. Indeed. All the more baffling for the sector — particularly bearing in mind the support that the nuclear industry had been promised — when that same support was not extended to this global pathfinder. I described that decision as unjust, and the resentment engendered by it still lingers in Wales — and will continue to do so, I suspect, for many years to come.

Subsidy for a mainstream sector?

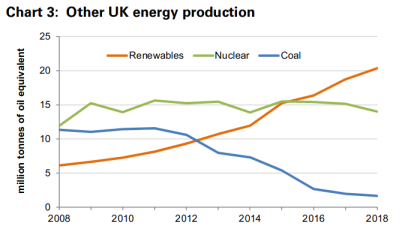

Few would argue that renewables have entered the mainstream as a major power producer. Indeed, those that would argue do so in face of the facts; in 2018 the output from renewables overtook the combined output from coal and nuclear.

It’s a trend which looks certain to continue, with the costs of renewable energy continuing to fall, and with UK Government support for offshore wind guaranteed for the medium term under a Sector Deal. Given this strong support for our offshore colleagues, it’s all the more disappointing to still be waiting for any sign that our nascent marine energy sector will see any kind of revenue support. And equally disappointing that the cheapest forms of electricity generation — onshore wind and solar photovoltaic — continue to be excluded from competitive auctions for subsidy.

Let us not forget, in the discussion about subsidy, that fossil fuels in the UK receive subsidies of around £15bn per year on average. Offshore wind will receive £557m per year under the sector deal, and large-scale onshore wind and solar will receive zero.

Given the headstart obtained by the nuclear and fossil fuel sectors, it’s astonishing to me that they should receive any subsidy at all. I would love to see those figures reversed. Let’s invest in our future instead of propping up our past.

Heat and transport

If electricity is a job partly undertaken, what of heat and transport?

It’s no surprise that neither sector have decarbonised significantly since 1990, wedded as we are to the infrastructure that supports the processing and distribution of the fossil fuels which underpin our heat and transport systems. The Committee on Climate Change gave their suggestions for Wales’ emissions targets for 2050, and specifically highlighted planning as an area which could tackle both heat and transport. How disappointing, therefore, to see developments continuing to spring up around Cardiff with little or no obvious mechanism to transport people and goods, except for the private automobile. We seem to be putting an awful lot of faith in the laissez faire approach to market development in clean transport, and insufficient regulation into obliging our developers to make our communities genuinely sustainable.

That’s not to say that we haven’t made progress — the latest version of Planning Policy Wales is a major step forward. And yet those housing developers who obtained their planning permission many years ago, and have been sitting on their precious land banks; they will be able to build to the same crappy standards they’ve been using for decades, condemning the occupants to a lifetime of high fuel bills. What power does our Future Generations Act have in preventing this? I call for a sunset clause on planning permission in the built environment — or at least a requirement for developers to adopt the latest building standards when they finally get around to developing their sites.

Final thoughts

My final comment is to urge you as an individual — and as an organisation — to sign up to your trade body or union. Our sector would undoubtedly be the poorer without RenewableUK’s policy, advocacy, media and networking activity. Even though I will no longer be an employee of RenewableUK, I will be tireless in advocating membership for it. Whatever your sector, there is (probably) a union or a trade body for you. Your membership enables the functioning of that organisation, to the benefit of the sector.

As an organisation, we are as flawed as any. But what wonderful, talented, inspirational and committed individuals they are that make up RenewableUK, and what an amazing difference this organisation has made to the sector, and to our society.

Wales, and the UK, are more prosperous, cleaner, and are stronger global players in the discussion around climate change because of the action of RenewableUK and other trade bodies in the sector — and, of course, because of the member organisations who make up those trade bodies. Colleagues in the energy sector, I salute you and your perseverance. My very best wishes as you continue to make this world a better place.